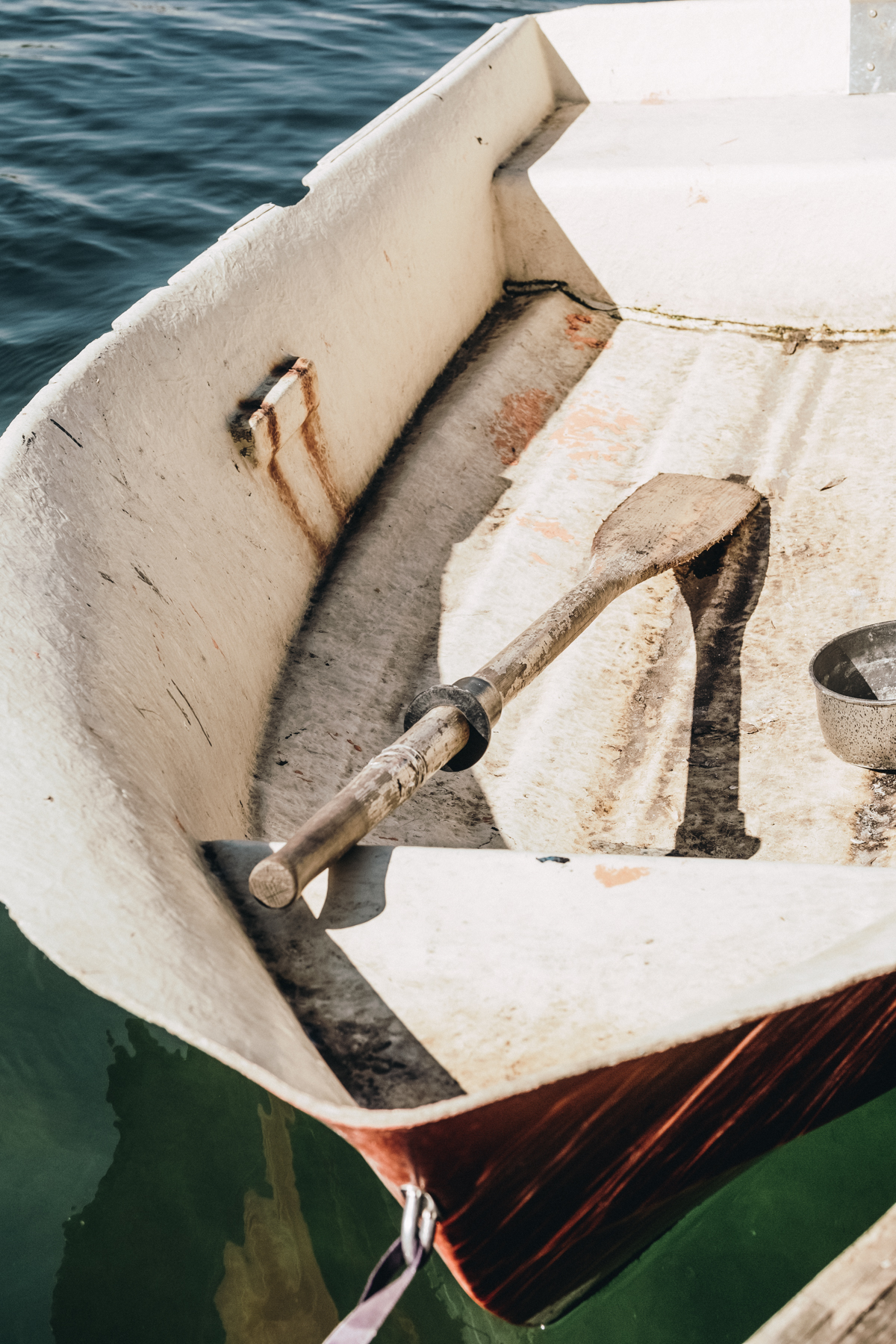

Among the wild reed beds close to Christiania beach in the south of Copenhagen, Lisa Weber docks her small dingy on a makeshift pontoon and ushers me aboard. Over on the opposite bank, I glimpse the upscale headquarters of Danish startup firms; behind them, Copenhagen Opera House looms in the distance.

“That’s Raphael,” she says, waving to someone in a small yacht as we paddle out. “His boat was towed away, so he took over that one. That’s kind of how it works around here.”

We’re headed for Lisa’s home and art gallery, one of the 40 or so anchored vessels that make up the community of Fredens Havn, known locally as the “Pirate Harbor.” Some of its residents have lived here for years; others come and go with the seasons. Lisa arrived in October 2016, a few months after starting her master’s degree.

|  |

| |

“When I first looked for a place, I used Facebook and, you know, all the typical stuff,” she says. “Then, a day before I was supposed to move into an apartment [in July 2016], they cancelled. So I was pretty devastated – like, shit! What am I going to do?”

From January, Lisa had been living at Floating City, an art collective in the south west of Copenhagen that provides tools, recycled materials, and water space to volunteers for ethical projects, including houseboat construction. Instead of lengthening her housing search, she chose to stay on and build her own accommodation.

Helped by a team of friends, Lisa designed a “carriage” shaped float with windows on all sides. But just as her plans were reaching fruition, she hit a snag: “I realized I couldn’t stay on Floating City’s water space because of [internal] conflicts,” Lisa reveals. “So a person who lived at Floating City told me I should go to the Pirate Harbour instead.”

|  |

| |

“The thing with Pirate Harbor, though, is there are bridges that close off the water space,” she adds. “You can raise the bridges, but the people operating them don’t like to let others in.”

The team decided to construct Lisa’s home in segments, then transport it by road to the new location. They worked almost entirely with recycled material; Lisa’s sole purchase was fourteen wooden roof beams. In October, they arrived on Christiania Beach with the structure. Lisa finally moved into her home in late November.

“The first nights were really stressful,” she remembers. “After four months of hard work, I was worried someone could come and just tell us to leave. Apart from that, it was really cold. We had a bottle of olive oil, and it was constantly solid. But it was still much warmer than outside because it was really well insulated.”

|  |

| |

Lisa adopted rudimentary methods for cooking and keeping warm during that first winter. “We used lots of tea candles to heat the float,” she says. “We had twenty tea lights going at the same time, and actually – maybe you don’t expect it – but it really helps. And also, if you have twelve tea candles and arrange them in a circle, and you take some aluminum foil, you can bring water to a boil.”

Over the following months, Lisa fabricated pieces of furniture and a wood fire heater, later adding a gas cooker, solar panels, and a compost toilet. With funding from Snabslanten, a cultural agency, she re-purposed her float as a public art gallery: the Floating Kitty Art Gallery, exhibiting photography, paintings, and commissioning murals. Besides these home improvements, she turned her attention to environmental conversation.

|  |

| |

“A lot of trash from Copenhagen’s waters ends up here; that’s just the way it flows,” Lisa explains. “Pirate Harbor has been cleaning up the shore before each spring. In February, we get together and pick up trash every weekend.”

This concern extends to the wildlife population. “The swans have a nest on those pieces of wood that we put in the water,” she says, gesturing to an area close to the reed beds. “They can only breed because we have put boats in the water that break the waves, and we have planks in the water that also protect the nests.”

Lisa argues steps like this demonstrate the community’s deep-rooted connection to the waterway. “I was in Australia just recently – when you talk of the indigenous people there, you talk of the traditional custodians of the land,” she says. “That’s kind of how I feel, especially when I talk with the person who’s lived here the longest. It’s not about owning the place or the land but about taking care of it and looking after it.”

Without ownership rights, however, the Fredens Havn community may soon have to abandon their homes. “I got news of an eviction, that some concrete action would happen, in February [2019],” she says. “They delivered letters to every boat. They had done this in past years, but this time it seems a lot more serious because we know there’s this huge state budget.”

|  |

| |

The channel where Fredens Havn sits isn’t a regulated maritime harbor; instead the state classes it as part of Denmark’s coastline. This means boats can lawfully anchor on the waterway for free without paying fees, just like vessels that moor out at sea. But kystdirektorat, the authority in charge, wants boats without a means of propulsion (a functioning mast or engine) to leave. The community recently struck a deal to remove a number of unoccupied crafts, but their collective’s future hangs in the balance.

This state of affairs contrasts with the fortunes of wealthy landowners in the country. In March, research institute Finans Denmark reported nationwide real estate had topped 2007’s pre-crash valuations; the country’s rental market remains one of the most competitive in Europe, ranked 7th. This inaccessibility has contributed to a rise in homelessness, with thinktank Kraka citing an increase across Denmark between 2010 and 2018 – weighted heavily among those aged 18 to 29.

|  |

| |

Lisa’s protest banner “Not Everyone Can afford a Villa” is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the city’s growing economic disparities. But what’s striking is how incongruous the statement seems amid its surroundings. Where once those with few options could settle on the sheltered waterway, today they’re vastly outnumbered by an increasingly affluent majority. These days it seems that many can indeed afford villas, while a rising number can’t afford or find housing at all.

Even if the eviction doesn’t go through, Lisa feels creeping gentrification could spell the end of the floating community. “This is a very creative place, and it’s a very inclusive and social place, where people can live who don’t have anywhere else,” she says. “I don’t feel very confident that places like this can survive in the future while there are new for-profit places opening up all the time.”