Why do so many people judge Stockholm to be one of the world’s most beautiful cities?

There are the people of course, but besides that, we think it’s the interplay between the natural and built environments. With its many islands, hills, and parks, the city offers stunning views of interesting buildings dating from every era of its long history.

Guide books and travel websites list the must-see architectural masterpieces, including City Hall, the Royal Palace, and the cathedral. The list may start there, but there’s so much more.

Here’s our favorite lesser-known architectural gems of Stockholm, each with its own story, waiting to be appreciated:

Piperska Muren

This historic home and its garden, located in what is now the dense urban environment of Kungsholmen, are relics of an earlier era when this part of Stockholm was an area of farms and country homes.

Piperska Muren, as the property is called, consists of two attached buildings. Though the earliest part of the structure dates to the 1690s and the buildings are attractive, what makes this site special is its beautiful baroque garden.

It includes well-trimmed hedges, lawns, classical statues, walking paths, and water features. This green oasis, originally enclosed by a stone wall, was a reflection of the wealth and prestige of its owner, Count Carl Piper. The wall is long gone, replaced by a more transparent iron fence, but it lives on in the name (muren is Swedish for wall).

Today, Piperska Muren is used as a conference center and is located across the street from the City Courthouse. The garden is open to the public (dogs not allowed), but there’s a bit of intrigue about its landlord. Since 1807, the site has been owned by Arla Coldinu, a fraternal secret society with maritime origins. This explains why the iron fence includes the letters “AC” set around an anchor.

Piperska MurenScheelegatan 14-16 |

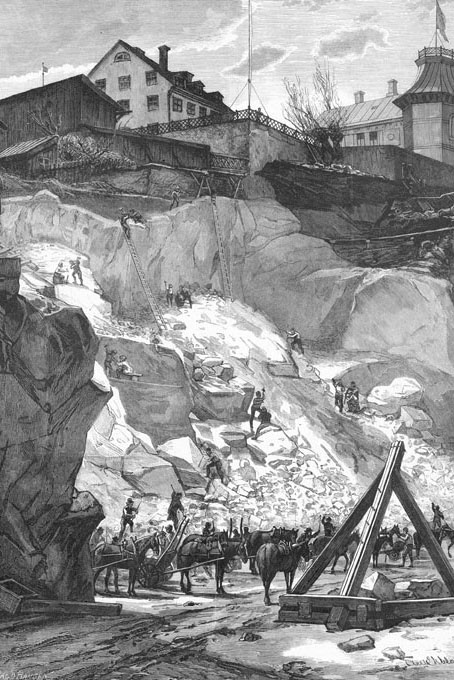

Mariahissen

This striking building on Södermalm’s northern waterfront resembles a Gothic church, with spires and brick arches, and stands alongside rock cliffs with hilltop buildings above it. Completed in 1886, it typifies the ornamental and historically inspired architecture of the Belle Epoque.

The building’s name, Mariahissen (which means the Maria elevator), clues us in to its origins. Its namesake lifts originally operated as a form of public transportation, charging a fare to carry passengers 28 meters (about 92 feet) from the low lying waterfront up to the Mariaberget (Maria hill) neighborhood above. The rest of the structure housed commercial uses, including a restaurant with views of the Old Town and Stockholm’s waterways.

|  |

Mariahissen’s Gothic spires emphasize its importance as a vertical structure. But, modeling it after church architecture seems an apt choice in other ways, too. This building, which was illuminated at night, epitomized the miraculous technologies of the new industrial age.

In this light, it’s fitting that architect Gustaf Dahl was inspired by religious precedents.

The public elevator service stopped in the 1930s and after a spell as a concert venue in the 1970s, Mariahissen now contains offices. Technologically, it is no longer cutting edge, but its beauty is timeless.

MariahissenSöder Mälarstrand 21 |

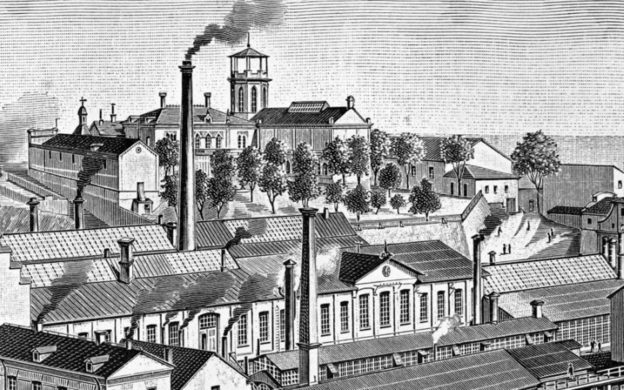

Münchenbryggeriet

In the mid-1970s, Stockholm’s mayor and city council approved plans to demolish this imposing and much loved former brewing complex and replace it with a new apartment development. Big mistake.

Opposition political parties latched on to public discontent over this issue and in the 1976 municipal election, the voters ousted the ruling Social Democrats from power for the first time in decades. Demolition, scheduled to start just days after election day, was canceled.

Besides the politics, this was also a major victory for grassroots historic preservation efforts. This followed several urban renewal projects in the 1960s and ‘70s that wiped out many notable older buildings across Stockholm and replaced them with Modernist architecture (more about that later in this article).

Located down the street from Mariahissen, the Münchenbryggeriet (Munich Brewery) started operating on this site in the 1850s and the current buildings were constructed in phases during the 1890s and early 1900s. The architect Hjalmar Kumlien blended Renaissance and Neo-Gothic elements which make the main building, over 250 meters long, look more like a palace or a fortress than a factory. Beer production ended in 1971, prompting the City’s redevelopment plan.

Today, Münchenbryggeriet contains offices, a conference center, the Royal Swedish Ballet School, and it hosts various cultural events. Located along the waterfront facing City Hall, it is a highly visible landmark and, for Stockholm’s politicians, should serve as a sobering reminder of the power of the people.

Münchenbryggerietoriginally Münchensbryggeri |

Gustaf Wickman’s Bank Row

Fredsgatan in Stockholm’s City Center is today a street lined by government offices, but many of its buildings were originally constructed in the early 1900s for banks from across Sweden. One of the leading bank architects was Gustaf Wickman, who designed three of the buildings.

Wickman’s first of these, from 1900, is the Skånes Enskilda Bank at Fredsgatan 7. Also known as Skånenbanken, this building embodied the Malmö-based company’s wealth and regional identity. Its thick red sandstone walls are from Övedskloster quarry in Skåne and its Baroque facade is full of sculptures and other decorations including fruit and vegetables, busts depicting “country folk,” and griffins – mythical creatures used in the coat of arms of Malmö and Skåne.

By comparison, Wickman’s other two buildings here are more restrained. Across the street from Skånenbanken is Sydsvenska Kredit AB at Fredsgatan 5, completed in 1909. Another Malmö bank, this one also used Övedskloster red sandstone but had a lighter touch in terms of ornamentation.

Down the street at Fredsgatan 4 is Sundsvalls Enskilda Bank, completed in 1902 for a bank based in northern Sweden. It has allegorical sculptures above its Art Nouveau entry gate, consisting of a man with an axe and woman with a paddle, representing the forestry and shipping industries, respectively. These were designed by sculptor Christian Eriksson, who also did much of the sculpting on Skånenbanken. He and Wickman later collaborated on Kiruna Church in Swedish Lappland, which in 2001 was voted the country’s favorite pre-1950 building.

|  |

Sundsvalls Enskilda BankFredsgatan 4 | Sydsvenska Kredit ABFredsgatan 5 |

Skånes Enskilda Bankaka Skånenbanken |

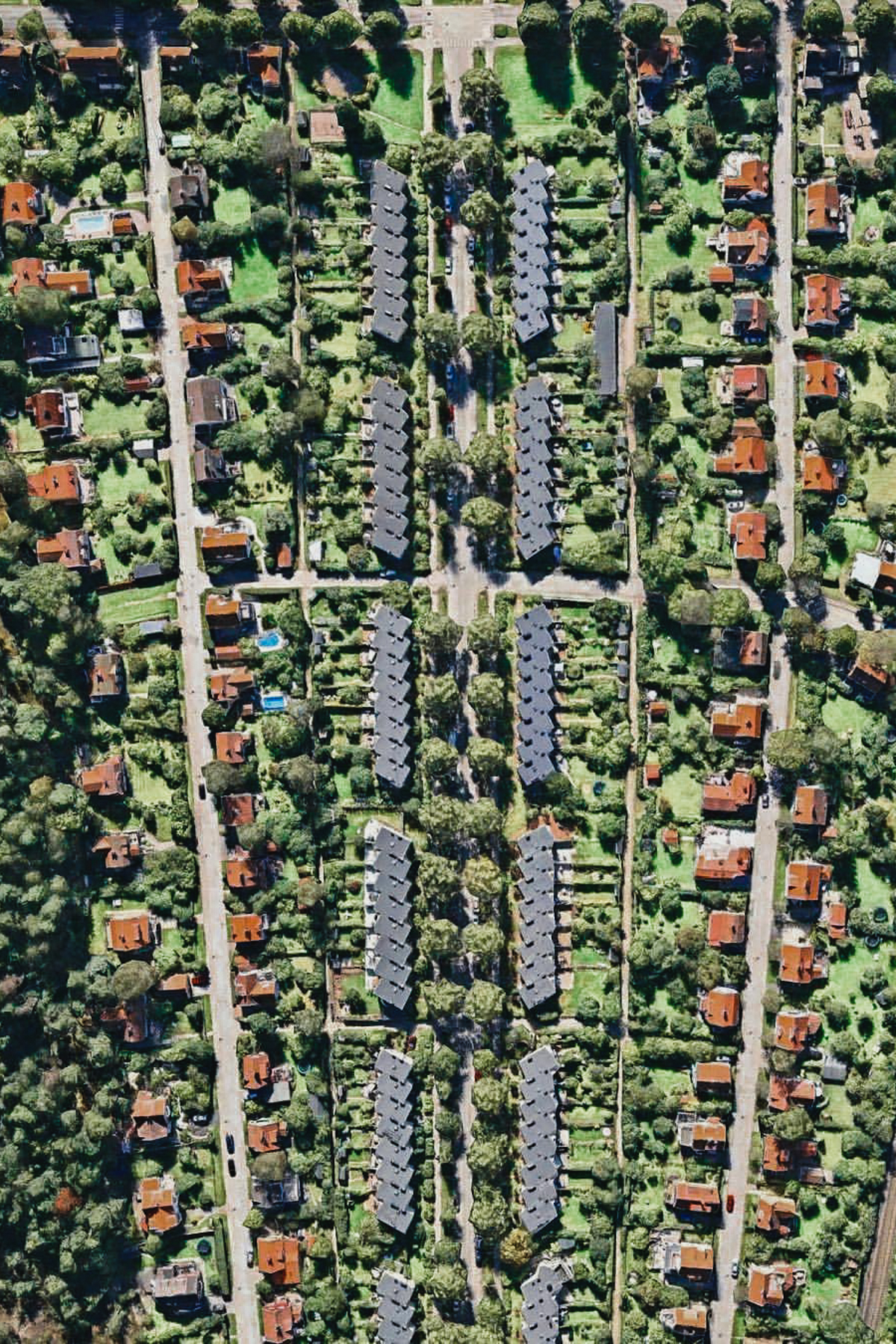

Ålstensgatan Houses

Reflecting the intersection of Swedish architecture and politics, Ålstensgatan in western Stockholm is lined by 94 Functionalist rowhouses from 1933 along what was once called the most democratic street in the world.

With their smooth white facades, flat roofs, and geometric shapes, the Ålstensgatan houses show a strong influence of Bauhaus design from Germany, but with a twist.

Rather than lining up side-to-side facing the street as one continuous wall, they are arranged diagonally, forming a zig-zag pattern. This arrangement by architect Paul Hedqvist creates a sense of motion and variation.

They were built by a private developer but with the purpose of providing affordable housing to the masses. One of the original residents was Per Albin Hansson, Sweden’s prime minister at the time, in a move that combined the personal and the political. This fit in with his call for a “People’s Home,” his vision for a Swedish welfare state where society functioned like a supportive family. Rather than a mansion, he lived in simple accommodation.

Actually, his home at number 40 is a bit bigger than the rest, though still relatively humble. He stayed there until he died in 1946 and the buildings are still known informally as the Per Ablin Houses, though nowadays they sell at a premium price.

|  |

Ålstensgatan 27-120Bromma, Stockholm |

Brunkebergstorg

Over the last couple of years, a new ultra-hip hotel hub has emerged in Brunkebergstorg in central Stockholm, revitalizing an area known for its austere 1970s Modernist architecture.

On the east side of this triangle-shaped public plaza, old banking offices have been radically transformed into the new Hobo and At Six hotels. They feature curated art, bespoke furniture, chic restaurants, and stylish guest rooms. Across the way is Downtown Camper by Scandic, a revamped hotel that blends urban adventure and glamping motifs. These new hotels face onto a redesigned pedestrian space with new benches, paving, and landscaping.

However, the architectural star of Brunkebergstorg, at least externally, remains the 1973 Riksbank (Bank of Sweden) which is notable for its textured facade of rough-hewn black granite with recessed windows. Stylistically, it’s far removed from Gustaf Wickman’s ornate banks, which are located nearby, but the use of stone echoes its predecessors.

The new lease on life given to thoroughly Modernist Brunkebergstorg is ironic. The buildings here were constructed as a result of an urban renewal program in which the city government demolished a number of historic gems in order to make way for a brave new Stockholm of the future. With historic preservation and adaptive reuse in vogue now, these buildings were saved from the wrecking balls that spawned them.

HoboBrunkebergstorg 4 | At SixBrunkebergstorg 6 |

Downtown Camper by ScandicBrunkebergstorg 7-9 | RiksbankBrunkebergstorg 11 |