Trigger warning: This article contains details of an alleged racially motivated murder.

The protests in the United States against police brutality have sparked a broader discussion on race and colonialism in Europe. In Denmark, much of the conversation has focused on hyggeracisme, or “hygge racism,” and the role it plays in perpetuating negative stereotypes and racist ideologies.

“I’ve only heard [the term hyggeracisme] maybe within the last couple of years,” says Mica Oh, a Danish activist and educator who facilitates anti-racism courses for universities and companies. “[But] for me I’ve known [about] it the last 25 years. Why? Because racism in Denmark is something we’ve been having ‘fun’ with. It’s sarcasm. It’s just for sjov. So, when we put racism in a category of ‘fun,’ we also put [it] in a category of hygge; and hygge is not just a word in Denmark. Danish people are hygge, and they want to maintain that position.”

While racism is not new in Denmark – despite what politicians say – the term hyggeracisme and its articulation is. According to Den Danske Ordbog, an online dictionary for contemporary Danish, the word first appeared in 2003 but no one seems to know where it came from.

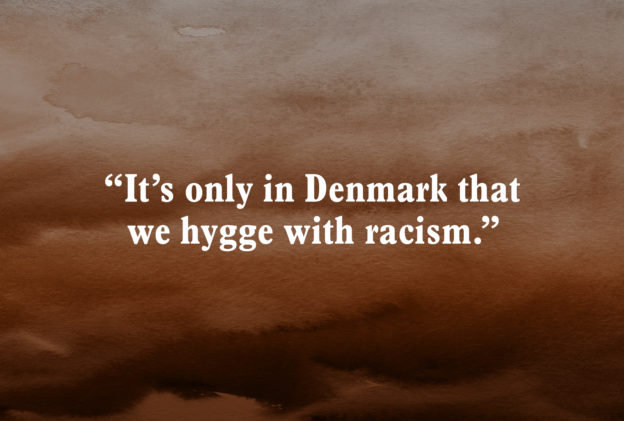

Hyggeracisme is personal. It’s within the family. It’s “civil.” It’s over a glass of wine. As Oh notes, “it’s only in Denmark that we hygge with racism.” This article explores how hyggeracisme operates in Danish society:

By pointing to the problem, one becomes the problem

Most people are familiar with the Danish concept of hygge and the image of candles and coziness it conveys. In fact, thanks to its rapid commercialization over the past five years, you’re likely to find the word “hygge” in Sydney, London, or New York. But hygge is more about a social atmosphere where all members participate: fun and conflict-free. It’s within this context that hyggeracisme happens; where one hears the N-word or sees a Nazis gesture in the name of “fun.” Since the state of hygge dictates a stress-free mood, anyone who speaks out is perceived as ruining the hygge. This is the person that is ultimately condemned by the group and vilified for breaking social norms.

“By pointing to the problem, one gets framed as the producer of the problem, and thus becomes the problem,” writes Danish historian and professor Mathias Danbolt. In his case study of the 2014 Skipper Mix licorice controversy (which, as a side note, you should read only if there’s nothing nearby to break or throw), Danbolt describes how the Danish practice of “racial exceptionalism” leads to a belief that Denmark is absent of racism. “Racism ‘proper’ is understood [within the Danish context] as something that primarily exists far away, in the past, or in the extreme right.” By defining racism as something from which Denmark is exempt, anything a Dane says or does can never be racist.

Another element to this is the normalization of “color blindness” which helps to preserve ideas around hyggeracisme being “harmless.” If Danes can avoid seeing or acknowledging racial differences, then they can, in effect, avoid the construct of race itself entirely. “This ignorance has nurtured a culture of ‘normative colour blindness’ that works to ensure that those who criticize racism appear as the ones who introduce race into the conversation,” Danbolt adds.

A major consequence of this belief in “Danish racial exceptionalism” is an unwillingness towards, if not contempt for, discussions on race. Suppressing any suggestion that racism, misogyny, or religious intolerance exist in Denmark has, in turn, allowed these prejudices to thrive in intimate and public circles.

A self-serving approach to history

I moved to Copenhagen in 2016, right before the centennial of Transfer Day; the day that Denmark sold the Virgin Islands – my home – to the United States in 1917. The event was commemorated with transatlantic celebrations, packaged as a period of post-colonial, self-reflection. In reality, what I saw looked more like collective cognitive dissonance; a “re-education” that conspicuously missed the point.

One example was the documentary Slavernes Børn (Children of the Slaves) that aired on Danish public television. The previews implied an hour-long show that would examine how the islands have changed since becoming an American territory. Instead, this “historical exploration” showed Danish reporters on an open water dive – all at taxpayers’ expense.

Also during this period, I Am Queen Mary was unveiled to much international attention. Three years later the “temporary sculpture” that was “the first part of an endeavor to raise a permanent bronze monument in the same location” remains unfinished, as does its accompanying “plaque” — a waterlogged, laminated piece of paper. Finally, a weeklong political debate around whether Denmark should issue a formal apology to the U.S. Virgin Islands concluded with a non-apology (no real spoilers there) and consensus that a regretful acknowledgment would accomplish nothing.

This summed up the general narrative around this historic event; less “national reckoning” and more “national remembrance of former wealth.”

|  |

Above: ‘I Am Queen Mary’ by Virgin Islands artist La Vaughn Belle and Danish artist Jeannette Ehlers. A monument of a rebel queen challenges Denmark’s forgotten colonial past.

What does this have to do with hyggeracisme? Everything, argues Maja Modekær Black, author of “Hygge Racism: ‘Noget Som Man Nok Bruger Mere End Man Tænker Over.’ A Qualitative Study of Well-Intentioned Racism,” the first qualitative exploration of hyggeracisme. She contends that this revisionist history is not an accident:

“An imperative aspect of racism in Denmark can be linked to its history as a colonial empire that lost vast amounts of land,” Modekær Black begins. By whitewashing its role in claiming people as property, a curated mythology about Denmark is able to endure. “This lack of [a] nuanced depiction of the harsh reality in the colonies has affected how Danes perceive themselves, their role in history and in a globalized world.

“Danish cultural identity is then based on [the] imaginaries of our doings in the world that is partly shaped by a self-serving approach to history.”

Oh echoes this sentiment in her anti-racism workshops, where we she challenges the Danish identity of egalitarianism. “The construction of Denmark is that we have a beautiful little country with all the privileges in the world. The curriculum [taught in schools] is not to tell the right story, but to tell the story so that we [Danes] can hygge.”

Black Lives Matter

The day before the Black Lives Matter demonstration in Copenhagen, which drew a crowd of 15,000, I was standing over a blank piece of cardboard. I wanted to create a sign that spoke to the Black experience, to what it’s like being a person of color living in Denmark. I needed Danes to know that anti-Blackness isn’t a monopoly and that there are serious problems here that also needed to be addressed. So, I bounced a few ideas off a group of friends and decided to scrap any mention of the word hyggeracisme. It seemed too new and too niche for mass consumption. To my surprise, the first woman I saw had a “Fuck din hyggeracisme”, or “Fuck your hygge racism,” sign.

|  |

|  |

Above: Images from the Copenahgen ‘Black Lives Matter’ demonstration, taken by the author, Jaughna Nielsen-Bobbit

“I believe that we’re gaining momentum here in Denmark,” Oh says optimistically at the end of our interview. “The schools have made it so that [Danes] understand the world in a certain way and then the media [and politicians] reinforce this belief. But I can feel that the next generation are hungry to learn: What is a micro-aggression? What is discrimination? Am I racist? Young people are tired of not knowing. We have this time now and we have to embrace it.”

I felt oddly encouraged after speaking with Oh; after learning that more and more Danes were revisiting their colonial legacy. Perhaps this was the moment that Denmark could turn the page?

Then a Black Dane was murdered on Bornholm.

On June 23rd, a 28-year-old Danish-Tanzanian man was found tortured and killed near a campsite on the Danish island of Bornholm. The two white Danish men arrested for this crime are brothers and one is a known Neo-Nazi supporter with a swastika tattooed on his leg.

Despite the gruesome nature of this murder and its similarity to the case of George Floyd in the United States, the homicide barely attracted the attention of the Danish press and Danish authorities were quick to reject that the crime was race-related – even while, by their own admission, they were still investigating the killers’ motives.

The response of the Danish authorities appear at first to be straight out of the “racial exceptionalism” playbook: dismiss or attack anyone who implies race could be a factor and repeat that racism is an issue that only occurs far away – in America, for example.

Hyggeracisme is often defended as harmless; something that is less overt or less serious than racism “proper.” But all racism is violent and all forms of racism lead to one place – violence.

My thoughts are with the family and friends of the victim.

This is an ongoing investigation.

Mica Oh is a Danish activist and educator who facilitates anti-racist courses for universities and companies across Denmark. You can follow her on Instagram at or contact her for course inquiries here.