The Danes are a straightforward people; they say what they think. At first, this might seem a bit rude to a foreigner, but slowly you realize that that’s simply the way it is here. What does this have to do with the Danish photographer Balder Olrik? This interview is a rare example of frankness, straight-forwardness, and open-mindedness.

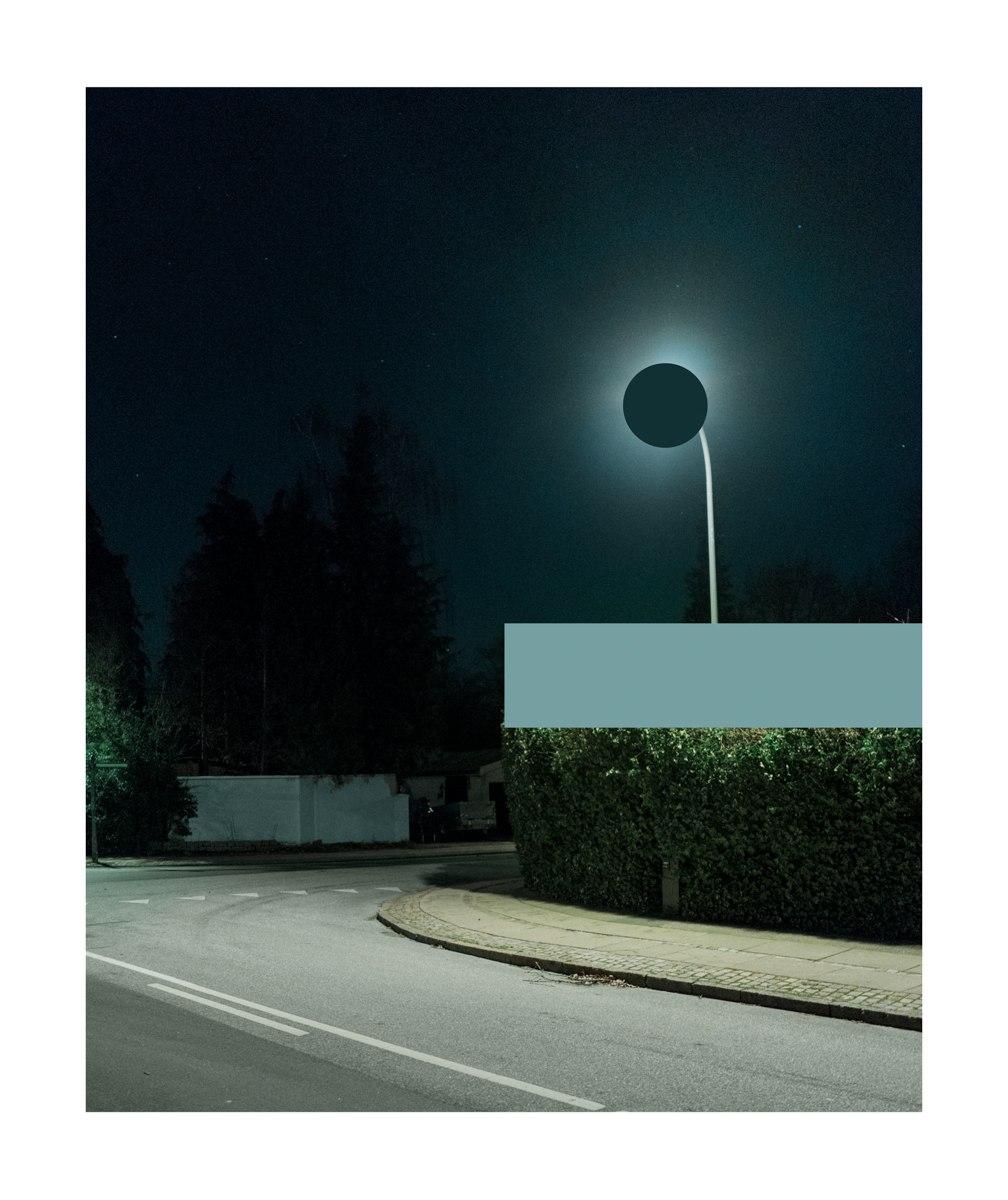

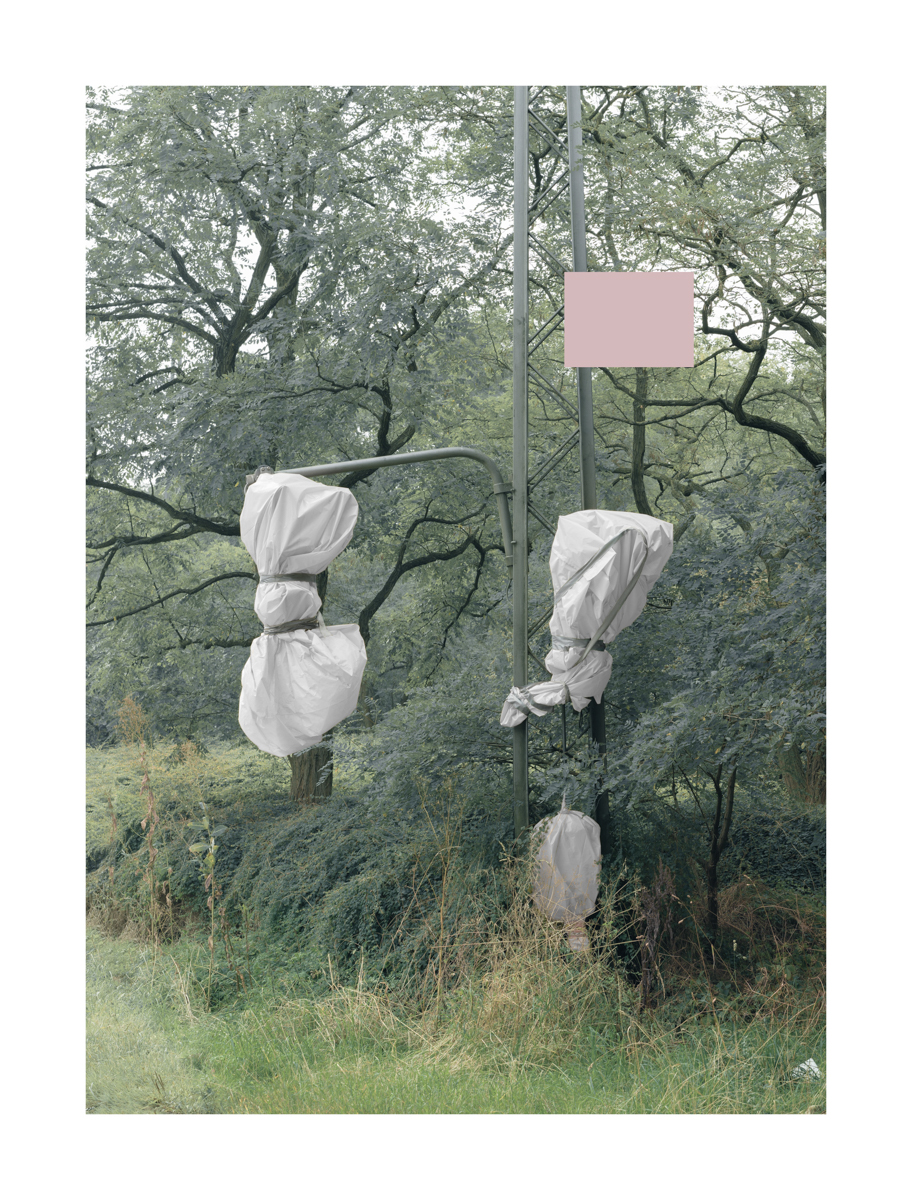

Balder tells us about the most intimate moments of his life, moments that others might have buried in their past. He chooses to share with us “intangible things” through his breathtaking photography. When looking at his photographs, one thing is for certain: he is way ahead of his time. Through his lens, we are able to see things that we might have never spoken about, even to ourselves. There is an ocean of photographs out there and there are even more background stories to those photographs. Balder Olrik’s photos, and especially his series “Under Reconstruction,” is something that has stayed in my mind for a very long time; it has changed me as a viewer. The story he shares, which is both funny and sad, is about a woman’s thoughts. At first, the images are confusing, but suddenly it becomes clear: of course! This story could not have existed without these images.

Join us for this story, and the story of Danish photograoher Balder Olrik himself, in his own works:

| |

|  |

When did you start photographing? Did growing up in the family of scientists influence your vision?

My fascination with photography started a long time ago. The very first book I bought was about women photographers’ views on women. I was so young then that I didn’t even understand the title. I just liked the images and was inspired to take photos by myself. But I was not really able to take anything that came up to my standards. So for many years, photography was kind of a notebook for my paintings. Around 1990, my interest in photography grew dramatically when I saw the possibilities of combining two mediums.

As you mentioned, I come from a family of scientists. Their jobs is to constantly tried to show us the secrets of the world. But I have always wanted to understand what is intangible inside us, at least in myself.

At an early stage, I understood that each person, whether it was a parent, a teacher, a friend or anyone else, had completely different perception of me. Most of them were in contradiction to what I felt or who I really was. But what was the truth? The mystery of human perception is something I’ve tried to understand all my life. It keeps popping up again and again in different forms. I was always questioning things. Simple observations can spin me out of the orbit for months until I return back with a set of souvenirs. That’s the essence of science for me.

I find your artworks very particular. Can we go back to ’80s when you were painting on canvas and continue to the ’90s, when you started merging paintings with photos?

My career as a painter exploded at a very early age. I was exhibiting internationally when my peers were still in high school. In a case like this, most artists would just try to live up to their success. But I just could not do that. For me, the reason for being alive lies in the unstoppable searching for answers. It happens every day. If you find me in those rare moments where I’m not like that, I am most likely in a state between desperation and depression. Photography, painting, and computers have been three main tools throughout my search. I wanted to find out how they materialize and how they differ.

|  |

In the late ’80s, my photos were darkroom-manipulated, but the technological developments in the ’90s expanded the possibilities. I bought a very expensive computer for image manipulation, as early as ’93, when most people, didn’t even know that it was possible to do digital image manipulation. It became completely integral to my creative process. Today’s excellent color printing pushed me to go further in that direction.

The series “System 2” deals with behavioral science and unconsciousness. What are the results of your investigation, and what is that we unconsciously choose to see or not to see?

I have learned much from using the theory System 1 & 2 in practice, and was able to take it further. Daniel Kahneman, who developed the theory of System 1 & 2 is not completely clear about what it is that triggers our shift from auto-perception to conscious-perception. I think I have a pretty good idea. It is basically when we miss some information to complete the picture. Another important thing I saw in the process was that we can learn to be conscious of our unconscious behavior. So you always know what state you are in. This enables you to make a shift and I think that it might be the single most important thing to learn today. If not, we will always be running after the yellow tennis balls like dogs.

If we asked a dog: “Why do you run after it?” It would probably answer: “It’s a yellow tennis ball man! I have to catch it!”

Yes, it might seem irresistible, but if we run after a ball every time somebody throws it, we are not free. We become dogs. In today’s media landscape, everybody’s throwing yellow tennis balls. Take Trump for example. Even clever people fool themselves into believing that it’s meaningful to read, post or comment on yet another crazy quote coming from him. Why? Just because he’s a madman doesn’t mean that you have to waste hours of your life on his foolishness. You haven’t changed the world even a bit by doing so. All you have accomplished is becoming yet another dog of his.

| |

|

The photos from your series “Stereo Vision” are pretty different from the rest of your photographs. Do those images have an undetected third dimension you would like to talk about?

The “Stereo Vision” images is an experiment about comparison. And it’s still in progress. Some of my earliest memories are of reading my grandmother’s gossip magazines as a child. On the second last page, there were two, almost identical, pictures. The task was to find five differences. I could look for them for hours. I didn’t understand why they were so hard to find.

The secret may be that you have to change your perception from looking at symbols to looking at shapes in order to see the difference. But at that time it was a mystery to me. I became curious about comparison more generally. We constantly compare ourselves with others to decide if we are “okay.” Why is it so hard to look at your self without comparing to others? I don’t know, but I have to dig further into it and it’s exciting!

A side-effect I’ve noticed while working on “Stereo Vision” is that I fell into a meditative state several times when I was looking at the pictures. My eyes began swinging like a pendulum from one side of the picture to another and suddenly I could do nothing apart from being with all those colors and shapes.

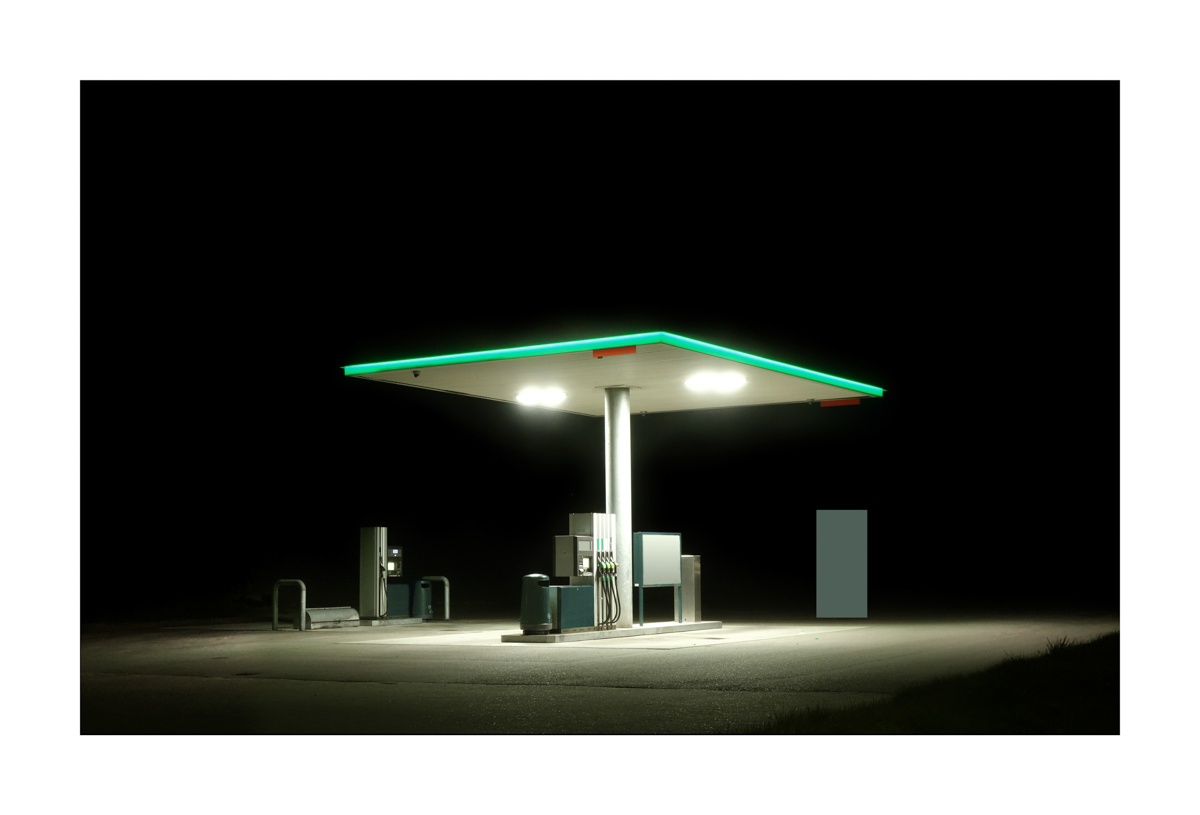

You photograph places that might appear melancholy to some. Where does all this solitude and sadness come from, what drives you to express your feelings in this poetic way?

At the age of nine, I was left outside the door of a foster home by my mother. She thought I was an evil child and she just wanted to get rid of me. Apparently, I drove her crazy by my presence. Today she likely would have been diagnosed with something on the Autism spectrum. When I got out, she gave the custody to my father only after 10 months. You have no idea how traumatizing it was. Most of the boys I met at the foster home either killed themselves or became drug addicts later in life. Working with art saved me; it was a way of healing myself from loneliness, sadness, and shame I felt inside. I forgave her completely. And even though I feel all of this belongs to the past now, it has somehow gotten into my handwriting. I can’t remove it.

|  |

| |

Do you think your photography is particularly Danish or Scandinavian? Why or why not?

Do you? It’s not an issue that interests me. I see artists in all parts of the world with whom I feel connected.

If we turn to your ’80s paintings, you often portray humans. In your later works, they seem to have disappeared. Where did they go?

Good question. I hope they will come back one day. I guess I found them problematic. Showing a person is not just showing a person. Each of us carries evidence of our time and social class. They couldn’t just be humans in a picture like I wanted them to be. For instance, let’s say you have a picture of a girl. I am quite sure you’ll be able to tell when it was taken with an accuracy of three years only by looking at her dress. You could also tell her social class pretty precisely. Even if naked, slightly less accurate, but you would still be able to tell these things. That’s a huge problem if it’s disturbing, or if it’s irrelevant to a story you want to tell.

What do you think of the current Danish or Scandinavian photography scene? Is it inclusive? Hard to get into?

Generally speaking, and this goes for all scenes.

If you come as an outsider and take a look inside, you’ll think: “Why don’t they let me into their circle?”

When you are inside the circle, you don’t really feel its existence. But I would say that photography is more open than other scenes. There are many possibilities to get your work out there. It often seems like a community of enthusiasts more than anything else. That’s probably related to the absence of money, which is both good and bad.

What are you working on now? Where can people buy your works, if possible?

Right now I’m working on a book. I’ve neglected the book format for years, so now is the time to do it. The good thing is that I am in a fantastic work flow. The “bad” thing is that I have turned away from my original idea of an art book. For now, I’ll go with the flow and see where it ends up.

Balder Olrik is represented by the Hans Alf Gallery in Copenhagen and Gallery Charlotte Lund in Stockholm, You can also find more information on his website.