Trigger Warning: the images below of products discussed in this article contain racist caricatures and stereotypes.

Boxes of cocoa powder, bags of coffee, and tins of vanilla sugar on the shelves of Danish supermarkets all have one thing in common: people of color are the logos.

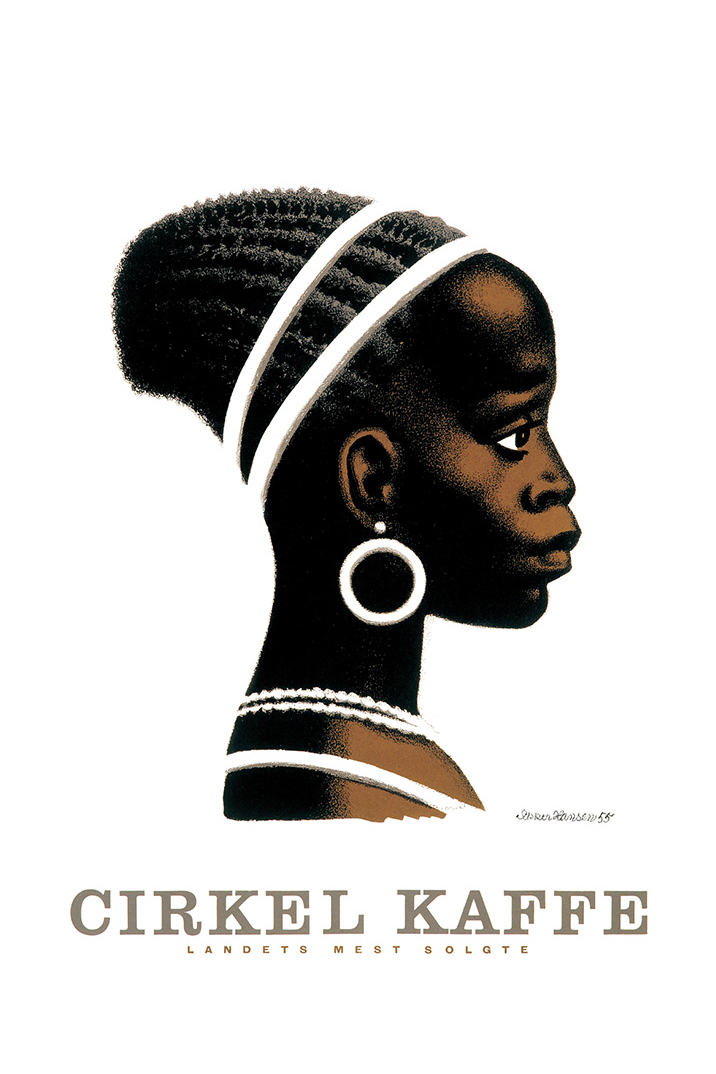

Busts of generalized African women or Asian caricatures are the literal faces of some of Denmark’s favorite food brands.

In many grocery stores, the section where such products are found is simply called “kolonial” (colonial).

In early 2021, Danish brand Tørsleff’s announced it would remove the turbaned Sri Lankan man who had long adorned its vanilla products and the Chinese chef from its jam preservative bottles. The decision came after years of Danish activists and scholars drawing attention to the stereotyped packaging. But other companies have chosen to keep similar packaging, despite criticism from social justice organizations and consumers alike.

“Many of these food products are imported from countries that have been colonized by Danish and other European countries,” said Trine Mee Sook Gleerup, an artist and longtime collector of these products.

“The imagery on the packaging refers directly to the power structure of the colonial period, reducing the people of the former colonies to exotic, hard-working bodies of color.”

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, many countries are being forced to reckon with with their colonial, racist pasts and presents. Experts say Danes’ relationship with these supermarket goods is complicated; just like Danish history.

A Conveniently Forgotten Past

In 2014, controversy broke out over a bag of licorice.

It started when the Swedish and Danish branches of candy company Haribo decided to redesign their Skipper Mix licorice after some customers called it racist.

The candies in question were tribal masks and caricatured faces meant to represent “souvenirs” a sailor might bring back from his voyage around the world, according to an article by Berlingske.

The faces all belonged to people of color and sported exaggerated, stereotypical features:

Above: Haribo’s Skipper Mix prior to their 2014 re-design

What followed was a public outcry, with a 4,000-person Facebook group formed to “support Skipper Mix,” over a candy that reminded many of childhood traditions.

The caricatures in the bag reminded art historian Mathias Danbolt of something else, though: the transatlantic enslavement trade.

In his study of the Skipper Mix controversy, “Retro Racism,” he pointed out how the design of the bag, with a white captain on the outside and his “goods” – including Black people, coins and weapons – inside, had all the central elements of the Danish enslavement trade. But the debate in Denmark, Danbolt noted, didn’t really focus on where this design was coming from. Instead, commentators railed against the “political correctness” of changing the licorice.

Activists say Denmark is often avoidant about the ugly parts of its past. “I’ve never met a nation that is so, so scared of looking at it,” Amaal Ruchti, board member of Afro Empowerment Center Denmark, said of racism in the country.

Denmark, long a seafaring nation, conducted almost 1% of the transatlantic enslavement trade from the 1660s to 1806. It was also a colonial power: for over 200 years its colonies included the Virgin Islands, the Gold Coast in west Africa, Tharangampadi in southern India, and Greenland.

During the height of its colonialism, Denmark-Norway engaged in what scholars call the triangle trade: trading weapons and equipment for enslaved Africans, bringing them to work in Caribbean colonies, then exporting the goods back to Europe.

This was where many “kolonialvarer” –– spices, coffee, sugar –– originally came from.

Denmark was not alone: colonial goods stores existed across Europe, and traces of them can still be found. In fact, the K in the name of the German supermarket corporation EDEKA stands for “Kolonialwarenhändler,” or colonial merchants. But today, this term has fallen out of use in many parts of the world besides Scandinavia.

Since it sold the Virgin Islands to the United States in 1917, Denmark seems to have forgotten on an institutional level its colonial and racist past, Danbolt said. But even though this past might not be widely discussed, packaging of sweets and dry goods put it “right in your face,” notes Mira Skadegård, a professor at Aalborg University who researches structural discrimination.

Danbolt said his job isn’t to call for the censorship of these items, though –– he just wants to draw attention to them. “Me, I’m mainly interested in asking questions,” he said. “I’m interested in why companies in Denmark today still think this is a good selling point.”

Why Colonial Branding Stays on Danish Supermarket Shelves

Colonial branding, in short, is still a selling point.

When Tess Thorsen, a representation researcher who teaches at Copenhagen University, tweeted criticism of a Danish ice cream company’s marketing, which she said fetishized colonialism and exalted “milkmaid whiteness,” other Danes pushed back. One commenter even called her a “female Hitler.”

Før vi får kollektiv orgasme (/ meltdown) over Hansen is der (endelig) skifter navn på én is, kan vi så snakke om hvor strategisk det er at skifte ét navn, for samtidig at overse deres malkepige-hvidheds-ophøjende-retro-racistiske-kolonialvare/kolonial-fetisherende nye kampagne? pic.twitter.com/pt8fQtLxRX

— Tess (@Tess_thorsen) July 16, 2020

Translation: Before we get a collective orgasm (/ meltdown) over Hansen ice cream (finally) changing the name of one ice cream, we can then talk about how strategic it is to change one name, to at the same time overlook their milkmaid-whiteness-exalting-retro-racist -colonial goods / colonial-fetishing new campaign?

Other Danes of color report being called “too sensitive” when they criticize colonial branding or address any racism in Danish culture. Activists call this phenomenon hygge racism, a mindset where someone who speaks out against racist acts in Denmark is seen as ruining the atmosphere or not being able to take a joke.

Such reactions, scholars say, are about the way many Danes understand racism, their country’s past, and themselves.

“The thing is with these products that we associate with goodness, or sweetness, like candy or theme parks,” Thorsen said. “It’s very, very hard for folks to shift that mindset or understand that that can be racist as well, regardless of intent or humor.”

Skadegård said she’s come across this misunderstanding often during her research on discrimination. It goes hand-in-hand with the widespread national belief that everyone is treated equally in Denmark, a concept called lighedsideologi, she said.

After all, Scandinavian countries have long been touted as uniquely progressive, happy, and trusting. According to many indicators, they are. Denmark can also correctly claim that it was never Europe’s biggest colonial power.

“We have this sort of deep-seated belief that there is equal opportunity for everyone,” Skadegård said. “So if you’re unable to experience equality, you might be the problem.”

And then there’s the myth that often infiltrates conversations about race in Denmark: the story that Denmark was racially homogenous until recently.

When ice cream brand Hansens changed the name of its “Eskimo” ice cream bars in the summer of 2020, it issued the following statement, reported by Ekstra Bladet: “We live in a new era where there is a good and healthy focus on minorities and inequality. A new light has been shed on what we call each other and how product names can reflect an old and more uninformed time.”

|  |

Left: Irma’s Kæmpe Eskimo; Right: Hansens Eskimo Is

Interestingly, this “new era” and “new light” came after over 40 years of the Inuit community saying that “Eskimo” was a derogatory word. The Inuit Circumpolar Council has long objected to the word because it traces back to a colonial and racist history, said Juno Berthelsen, co-founder and board member of Nalik, an organization that works on decolonization processes and raises awareness about Greenlandic history and issues.

In fact, people of color have been living in Danish society for hundreds of years. Enslaved people were brought back from the colonies and many Greenlanders have also moved or been brought to Denmark.

Thorsen said this narrative about Denmark having been homogeneously white until the 1970s, while incorrect, serves multiple purposes.

“It works both to uphold the story that Danes can’t help it if they’re racist, because it’s mostly a homogeneous country where we haven’t had to think about race for a long time,” Thorsen said. “But then it also works in what we could call a multiculturalist agenda, which sounds more like, ‘Now we’re very multicultural. Now we have to act and be more anti-racist because of these new immigrants.’”

In Carl Jones’s experience, a society’s advertising usually reflects what that society thinks, he said.

Jones is an advertising expert who is currently investigating how to decolonize advertising for his doctorate.

In order to remedy colonial advertising, he suggests that all types of people be involved in the creative process, “not just have the ruling class, which is usually the dominant class, the white colonists or European colonists making decisions on behalf of others.”

“I always notice that”

Even though white Danes may not think about their food packaging, many people of color in Denmark do.

“I always notice that,” said Mica Oh, an anti-racism educator. “If you’re a Black person and know a little bit about Black history, you can’t help it.”

Oh recently started Denmark’s first intersectional high school. She believes white Danes are not confronted with their past as colonizers, and hopes to build awareness through educating people in Denmark about Black history, anti-racism, LGBTQ issues, and intersectionality.

For Oh and other Danes of color, cultural blind spots in Denmark have real-life implications, such as apathy about their human rights or minimization of racist crimes.

In his work, Danbolt talks about how racial caricatures or racist imagery in Danish culture often seem invisible to white Danes. Similarly, activists find the Danish government often doesn’t “see” people of color, sometimes with tragic consequences.

Ruchti has been working for years with the Afro Empowerment Center to collect data on how many Black people live in Denmark, “because the Danish government doesn’t want to do it,” she said.

This is one of the factors leading to hate crimes going unrecognized by Danish police and the government, she said. The Afro Empowerment Center also combats racial discrimination in Denmark, which Ruchti said many Danes still don’t want to acknowledge.

“When you don’t see racism as a problem in society, then it’s hard to get human rights heard,” Ruchti said.

Arguments about colonial foods and their packaging often hinge on the idea that these products are “nostalgic.” But the colonial past is not as distant as some Danes might think, according to Berthelsen.

Although Greenland became part of the Danish kingdom in 1953, many structures from colonial times are still in place in Berthelsen’s home country. For example, in Greenland’s public administration and businesses, leadership positions are often still dominated by Danes, many of whom don’t speak Greenlandic, Berthelsen said.

Meanwhile, Greenlanders are often looked down upon and negatively stereotyped in Danish society.

“I want Danish people to know more about their colonial past, their colonial legacy, and how it affects non-white people or the people that they’ve colonized,” Berthelsen said. “Because even though colonization has officially or formally ended, all the repercussions from colonial brutality and suppression have lasting impacts.”

The Start of Change

Gleerup started collecting Nordic food packaging almost 20 years ago, from Finnish licorice sticks with Blackface images to jars of coffee with stereotyped silhouettes.

She did it to prove a point. “It was clear to me that a great number of food products used racist stereotyping on their packaging,” she explained in an email interview.

|  |

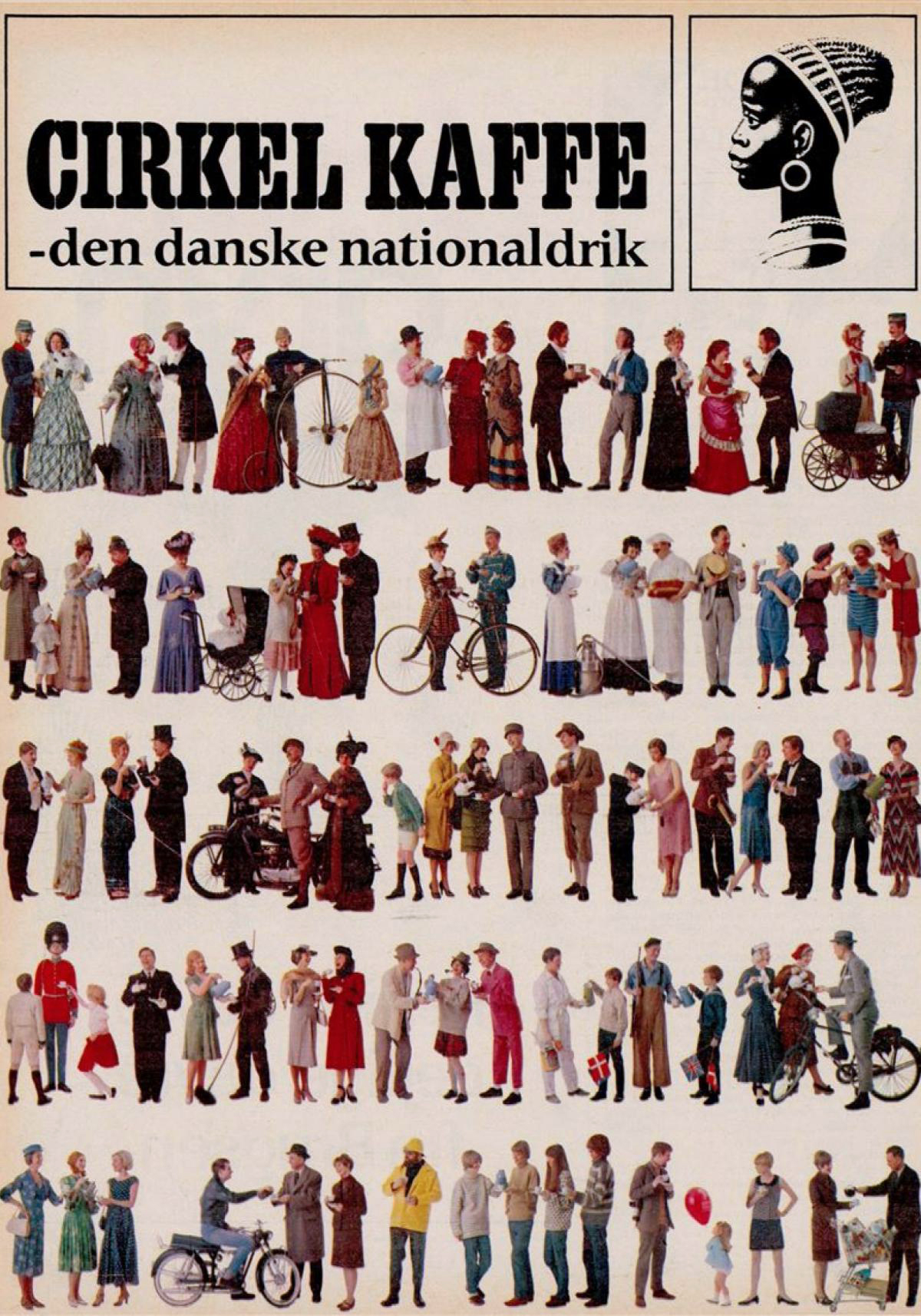

Over the years, Gleerup says she has seen a growing awareness of this kind of branding in the Danish public, and she’s curious to see what other brands will follow in changing their packaging: “Personally I’m waiting for Cirkel Kaffe to remove their current image too!”

But Cirkel Kaffe shows no motivation to change its logo of an African woman any time soon.

“We are very proud of the Circle Coffee Woman, created by the acclaimed Danish artist Aage Sikker Hansen, rewarded with Klassikerprisen by Den Danske Designpris 2004. I think he was inspired by where the coffee comes from, Africa. To day we produce the coffee on our own roaster-company in Kenya, African Coffee Roasters, which we have established in association with the local farmers to give them a more fair price for their beans. Our African colleagues are [also] proud of the logo,” said Jens Juul Nielsen, information director for Coop, in an email statement.

The relationship between Danish food brands and the countries they get their ingredients from has shifted over the years. Some brands that use generalized imagery of African women in their logos or advertising, such as Coop, Social Foodies, and Hansens, note that they partner with African farmers in what those brands describe as mutually beneficial ways. Some companies say their logos are simply inspired by where their coffee or chocolate comes from, declining to comment whether they were rooted in colonialism.

But many of Denmark’s iconic logos or food products –– including Tørsleff’s vanilla, Cirkel Kaffe, and the original Skipper Mix, trace back to the 1930s through 1950s. This suggests such marketing doesn’t stem from modern-day partnerships.

The woman on Cirkel Kaffe products, in particular, is a “national love object,” as Danbolt puts it. Many Danes hang it in their homes as artwork, seeing it as a beautiful image.

But it’s not an honor to Oh.

“If you knew that you as a state of Denmark has colonized, killed, knew the story about what happened, that you’re part of the story, would you say it was worship to put a Black woman in front of Cirkel coffee?” Oh said. “Or is it just a reproduction from the time of colonialism?”

Although some companies are beginning to reckon with such criticisms of their branding, the changes are often incremental. For example, although Haribo redesigned Skipper Mix faces to be less stereotypical, it still contains Mexicans, Africans, Chinese people, and Indians. The candy faced criticism again from a social anthropologist last year, who was quoted in Aftenposten saying, “One should not eat other people.”

To Gleerup, many brands’ attitude toward change is still troubling.

“When Tørsleff’s CEO, Henrik Andersen, says that, ‘It’s been a really hard decision [neutralizing the packaging],’ I find it very bittersweet, so to speak,” Gleerup said. “‘Better late than never’ is somehow fitting and somehow extremely understated in this regard.”

After years of activists and scholars speaking out, educating others and drawing attention to colonialism in Denmark, brands are beginning to take notice.

But the issue was never just about removing faces from logos. It’s about changing the attitudes and understanding of history that kept them there for so long.

“This is not an attack on white people,” Oh said. “And white people need to understand that when Black people speak up or address problematic things that are racist, that is not an attack on white people. That is telling the stories that they don’t know.”

Comments from brands

Hansens, Social Foodies, Tørsleff’s and Salling Group did not respond to our request for comment. Haribo declined to comment about the Skipper Mix controversy.

Disclosure

Tess Thorsen and Mira Skadegård are related, although we came to their work separately.

Note

Danbolt is currently writing about Gleerup’s 2014 display of her collection, which she called “Racial Representations.”

Header image by Freya McOmish, containing Cirkel Kaffe’s “Kaffepige”